On Worldbuilding: A Comprehensive Guide

Worldbuilding is hard, to put it mildly. It doesn’t matter if you’re a fantasy writer, or a contemporary fiction writer, you’re going to struggle with worldbuilding.

It’s pretty much on par with writing a book. Or even a short story, to be honest. After all, you want your readers to know where your story is set in. Generally, when I’m writing a short story, I like to set my characters in today’s world.

Of course, I would argue that short stories can be easier to write because you can choose to focus on a moment in time, or a particular scene only. But with novels, you can’t get away with it.

Your readers need to know if your characters live in an alternate history, a Narnia-inspired alternative dimension, or a Westeros-esque kingdom. It’s expected, really. And with that, you also have to give context to your world and why it’s being presented the way it is.

I think I can confidently say that worldbuilding is the hardest part of writing a novel. A good book will have its worldbuilding on lock. And this is extremely important because it can help your readers understand your characters’ motivations, their dreams, and why the stakes are so high.

So, if you’re struggling with worldbuilding—welcome aboard! I struggle with it as well. And so do a lot of writers. And to help you with this momentous task, I’ve created this blog as a guide on how to start worldbuilding.

The Key Elements of Worldbuilding

Writers—especially aspiring or new writers—can often get tied up in the details of the world they’ve built. It is so easy to get lost in the history of your world; the whys and hows and…everything else, really.

I’ve actually written over 400 pages, since the age of fifteen, just going into the history of the political system I’ve created in my story. Maybe someday I’ll release that—fingers crossed.

And this, I feel, is something a lot of writers might relate to. So, what do we do? Well, I think for your novel, even if the world is amazing and something you can totally get lost in, you need to take a step back and consider these key elements.

Before we proceed, I want to reiterate: you need to consider these key elements. Don’t do a deep dive just yet.

So, with that warning, here are the key elements:

1. Politics

As my favourite YouTube news show host, Philip De Franco once said, you may not eff with politics but politics will eff with you, and that is true for any good story. Your characters will be affected by the political situation in your book. Even if they live in an isolated community or a literal island, your world’s politics will mess with your character.

So, even if you’re not the most politically-inclined person, you need to think about it. Don’t go into too much detail, unless it’s a critical factor in your story. But go in just enough detail for readers to know what’s happening.

2. Religion

Religion, particularly in fantasy and dystopian settings, can play a major role in certain stories. It often goes hand in hand with politics. Depending on your story, religion can play a huge role in the plot, or none at all.

3. Economy

This doesn’t necessarily refer to the state of the economy of your world; more like, what kind of societal products or jobs you can find in your world. Fantasy novels will often have apprentices, while contemporary novels will feature everyday jobs. In addition to politics, the economy of the book can help your readers understand how well (or bad) off your character is, if they’re trying to climb the social ladder, and also help them understand the reason behind certain decisions.

For example, you have a character who has discovered that they’re a witch. If they’re in a small farm and their family’s struggling, learning this art can be a way to improve their family’s financial issues, or also help a struggling community.

4. Geography

Naturally, when you’re writing a story you need to know where your characters live. This could be a small town in the Midwest in the US, or a kingdom at war in a fantasy novel. Some stories can also be restricted to a single apartment unit or complex, though usually happens in some sort of murder mystery or psychological thriller where the main character is a hostage. Again, you’re the writer; you can choose to go into as much or as little detail as you want.

5. Culture and Language

Culture and language is again related to politics, religion, economy and also the geography of your story. This is, once again, something that would be more relevant to fantasy or dystopian writers rather than contemporary or even romance writers. Cultural heritage and language has often been a major player in establishing and defining nationhood in history, and the same can happen in your world.

If you’re writing about a revolution, the preservation of culture and language (as well as religion) can be a driving factor in the plot of your story itself.

6. Magic and Technology

Establishing magic systems and technology can make your story extremely interesting. And this is where you need to be consistent. Avatar: The Last Airbender and Legend of Korra, though TV shows, are excellent examples of stories where there’s this intricate magic system which influences technology. Your story can also either have a magic system or technology. Depends on the genre and what you’re going for.

Naturally, you—the writer—have full discretion in deciding which of these key elements need to play a major part in your story. Some stories might not need all of these elements, but having them at the back of your mind while you’re writing can definitely help you create a more consistent narrative.

And remember, consistency is key when you’re worldbuilding. Depending on how important these elements are in your story, you can go deeper.

A Comprehensive Look At Worldbuilding

With the elements out of the way, let’s go down this rabbit hole. I’ve included infographics in this blog because I know it’s going to be a long one. So, let’s get started. Beware: this is a marathon.

Part I: Laying the Foundation – Core Concepts

At its core, worldbuilding is about creating a setting that feels immersive; something readers can get lost in. As I explained in the previous section, you need to think about certain key elements and what role they’ll play in your larger story.

But before diving into the specifics of politics, geography, or magic systems, it’s essential to understand the foundational principles that will shape your world.

This includes the dynamics of class, the balance between realism and internal consistency, and the crucial role of interconnectivity. Let’s break this down.

Defining “Class” – Wealth, Power, and Status

Class is not a single variable but a system influenced by three primary components: wealth, power, and status.

These elements often overlap but don’t always align perfectly.

- Wealth: Financial resources and material assets.

- Power: The ability to influence decisions and shape events.

- Status: Social standing and prestige, often independent of wealth or power.

The interplay between these components creates complexity in any society. George R.R. Martin uses this dynamic to great effect. Tyrion Lannister is wealthy but struggles with status due to his family’s disdain. The Night’s Watch Commander has power over his men but little wealth. Varys, despite being low-born, wields influence in ways that surpass even kings.

When crafting your world, ask yourself:

- How do wealth, power, and status interact?

- Is social mobility possible, or are people confined to their roles?

- What historical or cultural factors determine class structure?

This all ties in with several of the key elements I talked about before, and there’s going to be a lot of interconnection there because things get messy. In a good way.

The Interplay of Realism and Internal Consistency

Realism is not the goal of worldbuilding—internal consistency is. Readers don’t need your world to reflect real history or physics; they just need it to make sense within its own framework.

- Realism provides structure to the unrealistic: If fire magic exists, what are its rules and limitations? If a kingdom thrives in the desert, how does it sustain itself?

- Internal consistency maintains immersion: If magic is rare, suddenly giving every character spells without explanation breaks believability.

As an example, the bending system in Avatar is entirely fictional but follows clear rules:

- Only certain people can bend.

- Each element has its own fighting style and philosophy.

- The Avatar alone can master all four elements.

This consistency makes bending feel natural, even though it’s unrealistic. Now contrast this with an unstructured world where systems and consequences don’t align. If a society has teleportation magic but still relies on horse messengers, readers will wonder why.

When building your world, ask:

- Does every element follow its own logic?

- Are there clear rules and limitations?

- If something changes, what ripple effects does it have?

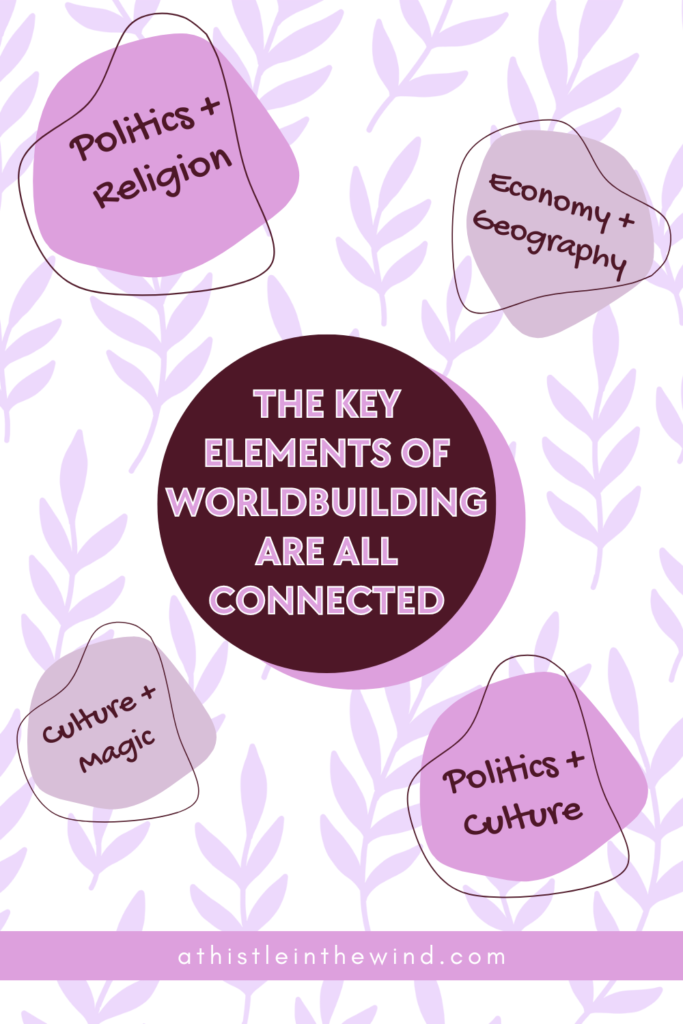

The Importance of Interconnectivity

No element of worldbuilding exists in isolation. Every detail—politics, economy, geography, culture—affects the others. Changing one should create ripples across the world.

- Politics + Religion: A theocracy likely enforces religious laws. Are heretics punished? How does faith influence governance?

- Economy + Geography: A desert kingdom must manage water scarcity. Do they trade for it? Is there conflict over resources?

- Culture + Magic: If magic is common, has it replaced traditional craftsmanship? Are there laws regulating its use?

Consider:

- How does each part of your world affect the others?

- Are there natural cause-and-effect relationships between elements?

- Does the world feel like a living system rather than a collection of disconnected ideas?

Starting Points for Worldbuilding

Not all worldbuilding begins with maps or government structures. Some authors start with a single idea—language, theme, or even a specific cultural detail.

For The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien built Middle-earth around his invented languages. In Howl’s Moving Castle, Diana Wynne Jones embraces whimsical, fairy-tale logic that gives her worlds a unique, organic feel.

There’s no right way to start.

Consider:

- A concept: A floating city with a rigid caste system.

- A theme: What if fate was a tangible force people could bargain with?

- A historical or cultural influence: A world shaped by nomadic traditions instead of settled empires.

The key is to let your initial idea expand naturally into something deeper.

Remember: Worldbuilding is Thematic

Just as a story explores themes, a world should reinforce them. Your setting isn’t just a backdrop—it should reflect and deepen the ideas at the heart of your story. The Hunger Games explores inequality and survival. The world’s rigid class system and brutal games reinforce these themes. A Song of Ice and Fire is about power, war, and betrayal. The feudal system, constant scheming, and political instability all serve this theme.

When building your world, ask:

- What central themes does my story explore?

- How can the world reinforce those themes?

- Are my world’s rules and conflicts tied to those themes?

Part II: Crafting Societies – Class, Power, and Social Structures

So, once you’ve set the foundations, you’ve got to consider the society your characters are born into. Societies form based on survival needs, labor divisions, and the ways power is distributed. For a believable setting, you need to consider how class systems emerge, how they are maintained, and how they evolve over time.

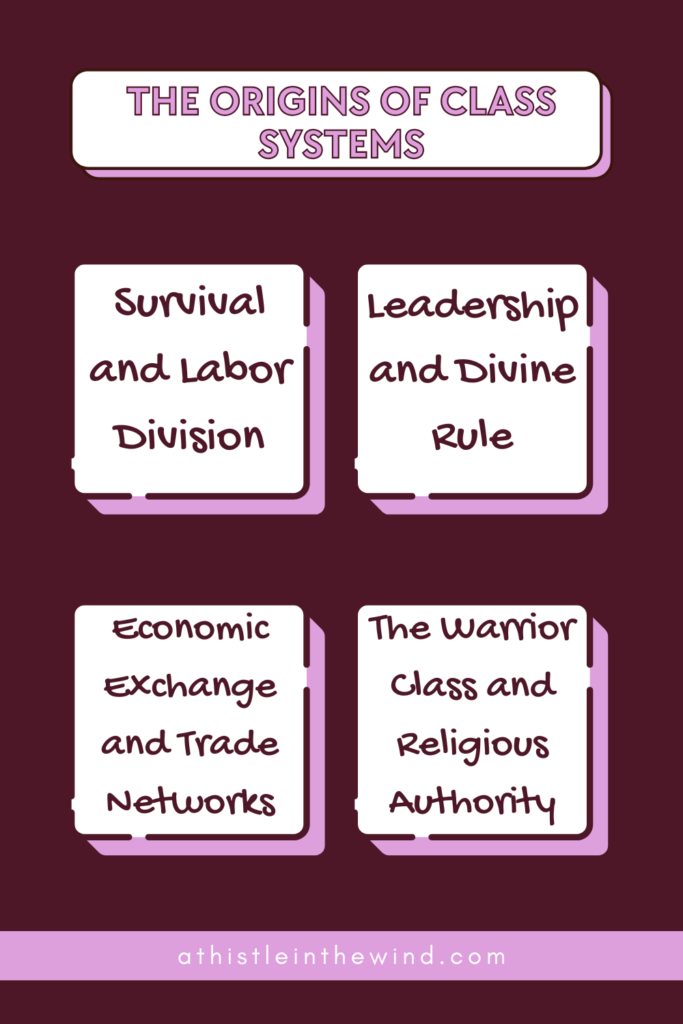

The Origins of Class Systems

Class systems don’t appear out of nowhere. They develop as societies grow, organize labor, and establish leadership structures.

- Survival and Labor Division: Early societies formed around agriculture, hunting, or resource gathering. Those who controlled food production or land naturally gained influence.

- Leadership and Divine Rule: Rulers often claimed divine legitimacy. Pharaohs of ancient Egypt were considered gods, much like how Fire Lord Ozai in Avatar: The Last Airbender tied his rule to spiritual power.

- Economic Exchange and Trade Networks: As societies expand, trade becomes important, leading to the emergence of wealthy merchant lords. In A Song of Ice and Fire, Illyrio Mopatis is a wealthy merchant-prince, one of many in the Free Cities.

- The Warrior Class and Religious Authority: Military leaders and religious figures often supported rulers. The Samurai in feudal Japan had both military power and a philosophical code.

Key questions for your world:

- What caused people to live in larger groups?

- How do rulers justify their power?

- What religious or philosophical beliefs shape class divisions?

Maintaining Class Structures

Once established, class systems don’t persist by accident. The powerful use a variety of methods to keep their status:

- Legal and Cultural Barriers: Laws that restrict land ownership, education, or certain professions to specific groups.

- Cronyism and Dependency: Keeping lower classes reliant on the wealthy through debt, patronage, or unfair labor practices.

- Violence and Ostracism: Public executions, exile, and criminalizing dissent.

- Monopolies and Artificial Scarcity: Controlling vital resources or trade routes.

- Propaganda: Stories and religious doctrines that reinforce social hierarchy.

Ask yourself:

- How do rulers and elites justify inequality?

- What myths, laws, or economic policies reinforce class structures?

- How do marginalized groups resist these systems?

How Magic and Technology Change Class Systems

Advancements—whether magical or technological—can shift class structures:

- Magic as a Tool of Control:

- In A Song of Ice and Fire, the maesters regulate knowledge of magic to maintain intellectual authority.

- In The Hunger Games, the Capitol controls technology to keep the Districts weak and dependent.

- Technology Empowering the Lower Classes:

- Printing presses in the real world led to the spread of knowledge and uprisings.

- In Star Wars, droid labor replaces certain human roles, raising questions about rights and exploitation.

Consider:

- Who controls access to magic or technology?

- Does it level the playing field or widen class divisions?

- How do elites react when their control is threatened?

How Class Systems Change or Fall

Class systems can shift in several ways:

- Peaceful Change:

- Lowering barriers to education, wealth, and political participation.

- Cultural shifts in how people perceive class (e.g., the abolition of monarchy in many nations).

- Revolution and Uprising:

- Economic hardship often triggers revolts (The French Revolution, The Hunger Games).

- Discontented elites may join the cause (A Song of Ice and Fire’s War of the Five Kings).

- War and Economic Shifts:

- Wars mobilize new social groups (The Hobbit: The destruction of Smaug shifts power back to Laketown and the Dwarves).

- Trade and industrial shifts weaken old aristocracies.

- Plague and Population Collapse:

- The Black Death gave peasants in Europe more power due to labor shortages.

- In The Way of Kings, magical healing and divine powers change who has access to status and survival.

Ask yourself:

- What forces (war, famine, ideology) might destabilize your class system?

- How do different groups react to social change?

- Is change gradual or explosive?

The Persistence of Class History

Even when class systems change, their effects linger:

- Language and Titles: Old noble titles may persist even after their power fades (The Lord of the Rings’ Gondorian nobility).

- Political Structures: A revolution might remove kings, but bureaucracies remain (The Hunger Games: The transition from the Capitol to District 13 still maintains centralized control).

- Cultural Memory: Generations later, people might still feel pride or resentment over historical class divisions (Avatar: The Last Airbender: The Fire Nation’s imperial past still affects its citizens).

Ask yourself:

- How do past class structures affect modern politics?

- Are certain traditions or biases left over from a bygone era?

Internal Conflicts: Class Tensions in an Empire

Nationalistic empires often struggle with internal class conflicts:

- Noble vs. Commoner: Do elites truly care about national unity, or just their own status?

- Colonized vs. Colonizers: Is there resentment from conquered peoples? (Star Wars: The Empire exploits entire planets for resources.)

- Loyalists vs. Revolutionaries: Do some believe in reform while others want destruction?

Consider:

- What factions exist within the ruling class?

- Do different regions or cultures resist the dominant order?

- Are tensions bubbling under the surface, or are they openly violent?

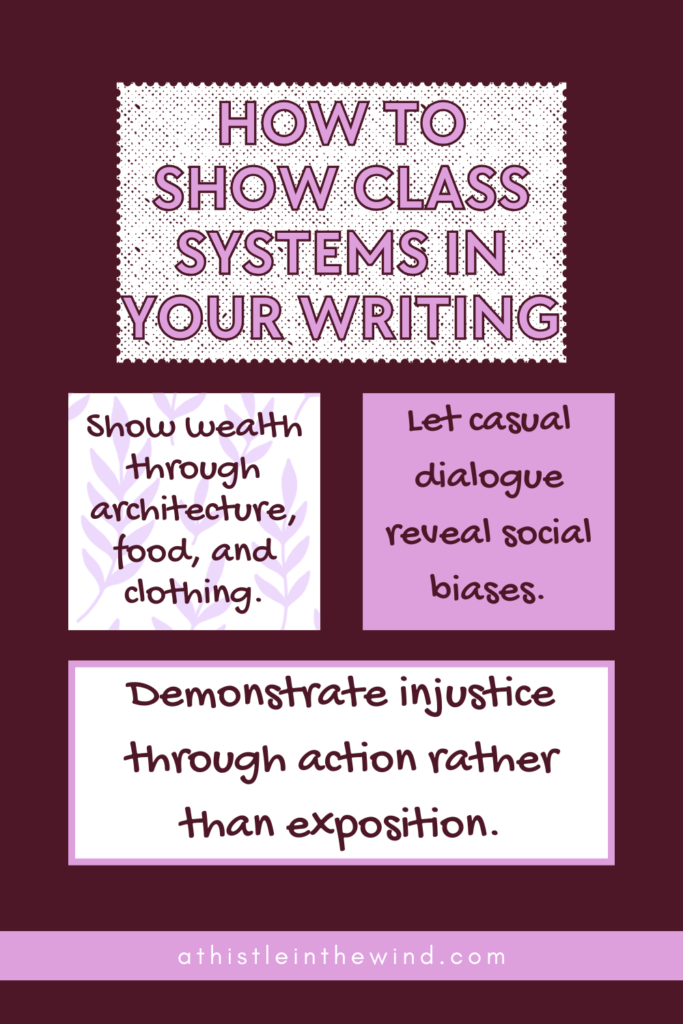

The Importance of Showing, Not Telling

Readers should feel class dynamics rather than be told about them:

- Use small details: In The Way of Kings, men aren’t meant to read or write, showing gendered class restrictions subtly.

- Character interactions: The way nobles speak to servants tells you about class attitudes.

- Environmental storytelling: Are slums overcrowded while palaces have empty halls?

For example, in The Hunger Games, the opulence of the Capitol vs. the suffering of the Districts tells us everything about class disparity.

Ways to integrate class dynamics naturally:

- Show wealth through architecture, food, and clothing.

- Let casual dialogue reveal social biases.

- Demonstrate injustice through action rather than exposition.

Part III: The Rise and Fall of Civilizations and Empires

Fallen Civilizations

Fallen civilizations leave behind relics, ruins, and remnants that shape the present world. These remnants can be more than just physical artifacts—they influence politics, culture, and even myths.

1. The Shadow of the Past

Even when a civilization is long gone, its influence lingers. The ruins of the past can be used to reinforce power, create religious sites, or act as a cautionary tale. In Horizon Zero Dawn, ancient technology from a fallen civilization still affects society, with remnants of AI-driven machines shaping the new world’s mythology. In The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin, remnants of past civilizations hold knowledge that characters struggle to understand, adding depth to the world’s history.

2. The Political and Social Influence of Ruins

- Relics and ruins can be sources of religious worship — The Lord of the Rings and the remnants of Númenor’s influence on Gondor.

- They can be used as propaganda to assert legitimacy — A Song of Ice and Fire, where houses claim ancestry to fallen empires like Valyria.

- They can serve as economic assets, driving tourism or trade — Howl’s Moving Castle, where remnants of war technology shape the world.

3. The Outside Context Problem

This occurs when a civilization is confronted with something far beyond its experience—whether it’s an advanced alien race (Star Wars, with the Republic encountering the Sith) or a natural disaster (The Fifth Season, where seismic events continuously reshape society).

4. Causes of Collapse

Civilizations fall for many reasons, often a combination of factors:

- Natural Disasters: Earthquakes, droughts, or plagues. Think of Avatar: The Last Airbender, where Sozin’s Comet enables the Fire Nation’s dominance, disrupting global stability).

- War and Conquest: External invasions or prolonged conflict. Think of The Hunger Games, where rebellion against the Capitol leads to societal collapse and restructuring).

- Hubris and Overextension: Civilizations collapse when they become too large to sustain. Think of A Song of Ice and Fire, where Valyria’s overreach led to its doom).

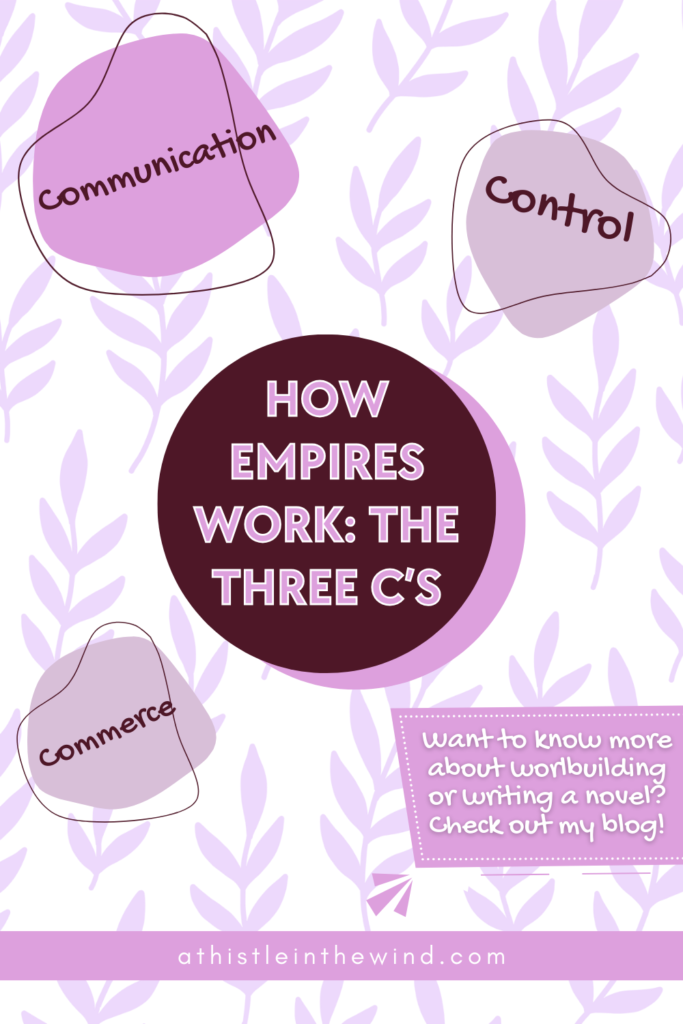

How Empires Work: The Three C’s

Empires thrive based on Communication, Control, and Commerce—losing one often leads to collapse.

1. Communication

- Empires require fast and reliable communication to govern vast territories (The Roman Empire with its roads, The Mongol Empire with its relay system).

- Poor communication leads to misinformation and chaos (Star Wars, where the Rebel Alliance exploits gaps in Imperial bureaucracy).

For example, in The Hobbit, the slow spread of information allows Smaug to terrorize the Lonely Mountain uncontested for years.

2. Control

- Control isn’t just about military might; it’s about making it preferable to stay in the empire. History shows us the British Empire’s use of infrastructure and economic incentives.

- Empires balance force and diplomacy. In A Song of Ice and Fire, Daenerys struggles between liberating and ruling conquered lands.

In Avatar: The Last Airbender, the Fire Nation uses force but also infrastructure and cultural assimilation to maintain dominance.

3. Commerce

- Trade routes and economic policies keep empires strong. Another historical example is the Silk Road’s importance to the Mongol and Roman Empires.

- Economic collapse is a major cause of decline. Think of Star Wars: The High Republic, where the breakdown of hyperspace routes disrupts galactic stability.

In Howl’s Moving Castle, merchant networks and magical contracts underpin economic relationships.

The Rise of Empires

Empires form due to several key motivations:

1. Resources

Empires seek control over valuable materials like gold, spices, or magical elements. In The Hobbit, Erebor’s wealth makes it a target. The desire for resources often drives war. You can see this in the A Song of Ice and Fire, where the Iron Throne is fought over because of its wealth-generating capabilities.

2. Security

Empires form to protect against external threats. From history, you can note that the Qin Dynasty in China unified warring states for stability. Defensive expansion can lead to empire-building. In The Hunger Games, the Capitol maintains a strict district system to prevent rebellion.

3. Nationalism & Cultural Unity

Empires often center around a leader who unifies people. In Avatar: The Last Airbender, the Fire Nation’s nationalism fuels its imperial expansion.

4. Technological Advantage

New technology can give an empire an edge. In A Song of Ice and Fire, Valyria’s dragons provided an unmatched military advantage, leading to its dominance.

The Fall of Empires

Empires rarely fall overnight; decline is usually gradual.

1. Fracturing & Revolution

Empires often break apart from internal dissent. The Roman Empire split into East and West. In The Hunger Games, internal rebellion gradually dismantles the Capitol’s control.

2. Succession Crises

A lack of clear succession creates instability. In Star Wars, the Empire struggles after Palpatine’s death due to power struggles.

3. Breakdown of Communication

Too much or too little communication can weaken imperial authority. In A Song of Ice and Fire, the Night’s Watch’s warnings about the White Walkers go ignored due to political gridlock.

4. Economic Decline & Disease

Economic failure can bring an empire to its knees. Similarly, plagues can destroy populations and weaken control. In The Fifth Season, environmental catastrophe disrupts economies and weakens entire civilizations.

Part IV: Populating Your World – Races and Cultures

Once you’ve built the world for your story, you can now start populating it. Here’s how.

Create Unique Races

In fantasy and sci-fi, “race” often refers to distinct species rather than human ethnic groups.

- Internal consistency matters more than strict realism—ensure that your races make sense within the logic of your world.

- Starting points for designing races:

- Cultural templates: Many races are inspired by real-world cultures (e.g., Tolkien’s elves draw from European mythology).

- Visual motifs: Consider how clothing, architecture, and technology define a race (e.g., the regal, high-gown-wearing elves in The Hobbit).

- Mythological archetypes: Many races emerge from existing legends, like dwarves being skilled miners and blacksmiths.

Overlap is inevitable—it’s okay to use familiar ideas as long as they feel fresh in your setting.

Biological Pressures

- Every species is shaped by three fundamental needs:

- Feeding: What do they eat? How does this impact their culture? (e.g., Wookiees in Star Wars and their arboreal lifestyle.)

- Reproducing: Do they have long lifespans or rapid generations? (e.g., Ents in The Lord of the Rings reproduce slowly, shaping their cautious nature.)

- Not dying: How do they protect themselves from threats? Do they have exoskeletons, camouflage, or healing abilities?

- Environmental Pressures shape physiology:

- A desert species may have water-storing adaptations (e.g., Fremen in Dune).

- A high-gravity world may lead to stockier, more muscular beings.

- Use these pressures to create unique species that feel organic within their environments.

Culture: The Heart of Worldbuilding

- Culture is everything. A species’ way of life is more defining than their biology.

- Biology affects culture but doesn’t dictate it:

- A long-lived species might have slow-moving political systems and artistic traditions (e.g., elves in The Lord of the Rings).

- A hive-mind species may develop collective decision-making (e.g., the Borg in Star Trek).

- Culture is complex—it doesn’t just mirror its environment.

- The Wraith in Stargate Atlantis are biologically driven to feed on humans, but their culture is shaped by power struggles and hierarchy.

Universal Pressures

Some factors shape civilizations regardless of biology:

- Technology: Space-faring species must develop starship construction and interstellar diplomacy.

- Social hierarchy: Even insectoid species may have caste systems or leadership structures.

- Resource scarcity: Wars and alliances often stem from competition over food, water, or minerals.

- Spirituality: Do they have religion? If so, what is its basis?

Racial Coding: Avoiding Clumsiness

Racial coding refers to when fictional species draw too heavily from real-world racial stereotypes. Avoid making one race “all good” or “all evil” (e.g., Star Wars’ Empire is largely human-centric, but not all humans are villains).

How to avoid racial coding pitfalls

- Make each race internally diverse—not all elves should be wise and noble.

- Give multiple perspectives within a single race—characters should have different opinions, ideologies, and conflicts.

The “Planet of Hats” Trope

A common mistake in worldbuilding is making every person in a race or civilization share the same culture, beliefs, and attitudes. An example of this are the Klingons in early Star Trek who were all warriors.

How to avoid it:

- Show regional and ideological diversity within a species.

- Horizon Zero Dawn does this well by making tribes distinct but also internally varied.

- Introduce different factions, subcultures, and personal beliefs.

By applying these techniques, you can create a world populated with rich, diverse races and cultures that feel lived-in and unique.

Part V: Political Systems, Religions, and Ideologies

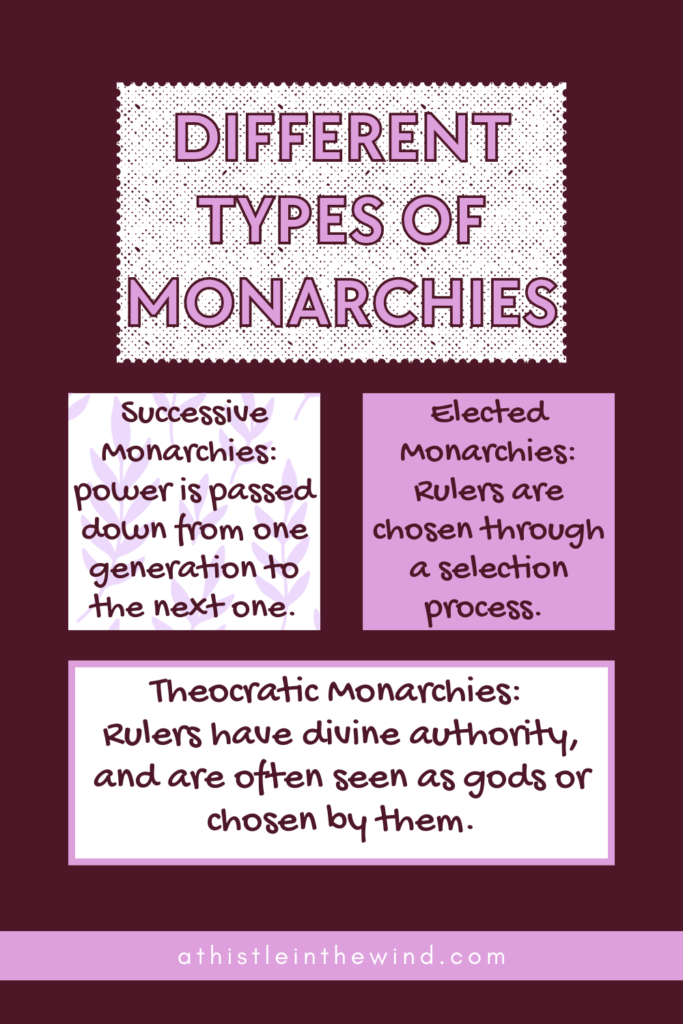

Monarchies

Monarchies are a staple of fantasy and historical fiction, but not all monarchies function the same way. Understanding their mechanics helps create more believable worlds. There are several types of monarchies.

- Successive Monarchies: Power is passed through hereditary lines, often leading to dynastic rule. Examples:

- A Song of Ice and Fire: The Targaryens and Lannisters rely on bloodline legitimacy.

- The Hobbit: Thorin Oakenshield’s claim to the throne is based on lineage.

- Elected Monarchies: Rulers are chosen through some selection process rather than inheritance. Examples:

- The Holy Roman Empire: The emperor was elected by powerful nobles.

- Star Wars: Naboo’s monarchy elects its queens, as seen with Padmé Amidala.

- Theocratic Monarchies: Rule is justified through divine authority, with monarchs often seen as gods or chosen by them. Examples:

- Ancient Egypt: Pharaohs were considered living gods, ruling as both political and religious leaders.

- Warhammer 40K: The Emperor of Mankind is worshipped as a divine figure, centralizing power through religious devotion.

Power and Stability

Monarchies are rarely absolute; real power depends on control over wealth, resources, and key supporters.

De jure (legal power) vs. de facto (actual power):

- A Song of Ice and Fire: The king’s power is often undermined by the nobles who hold military and economic control.

- Avatar: The Last Airbender: The Earth Kingdom king has little actual authority due to secret political influences.

Royal courts play a key role in governance, housing advisors, nobles, and spies who shape policy. Environmental and cultural factors shape a monarchy’s survival more than just a bad ruler. In Howl’s Moving Castle, monarchs are entangled in war and bureaucracy, showing the complexities of ruling.

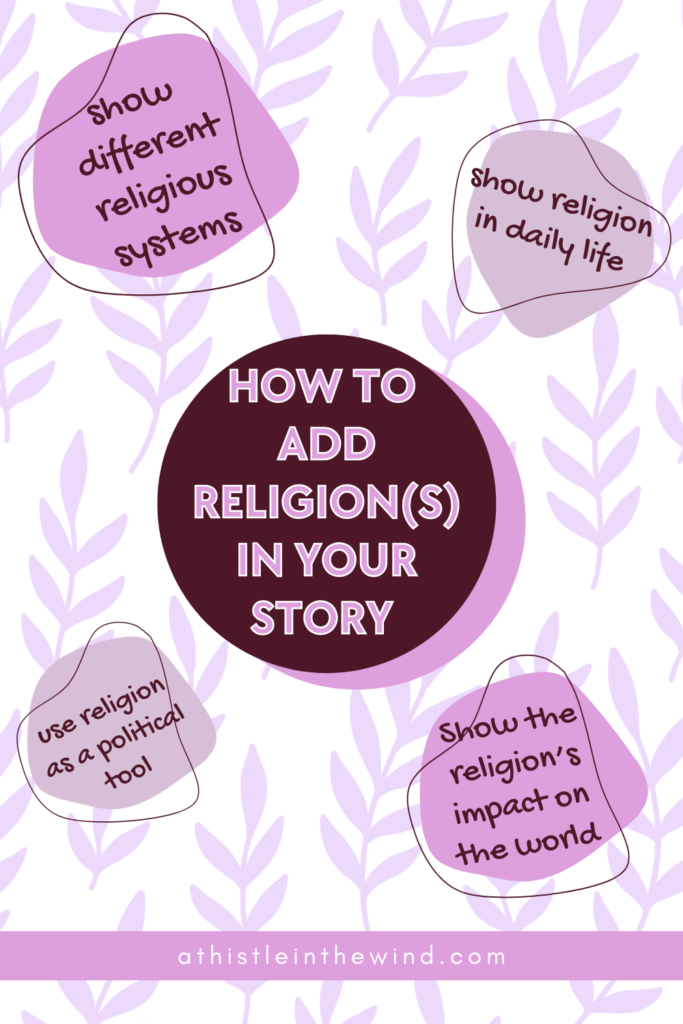

Religions

Religion is often woven into political and social structures. A well-designed religion adds depth to worldbuilding.

1. Show the Impact of Religion in Your World

Integrate beliefs naturally through characters’ actions, traditions, and conflicts. In The Hunger Games, the Capitol’s propaganda and cult of personality around Snow serve as a pseudo-religion.

2. Explore Different Religious Systems

You can make the religion(s) in your world interesting by exploring different religious systems.

- Polytheistic Religions: Tend to be more adaptable and absorb beliefs over time. The Elder Scrolls series shows how different races adopt and modify religious traditions.

- Monotheistic Religions: More rigid, often requiring strict adherence. Dune showcases a monotheistic faith with deep political influence.

3. Religion in Daily Life

Consider how faith shapes everyday activities, festivals, and taboos. Religion doesn’t need to answer all existential questions; it can be mysterious and inconsistent. The Hobbit doesn’t explicitly showcase religion, but rituals like Thorin’s burial hint at cultural spirituality.

4. Religion and Politics

Religion can be a political tool:

- A Song of Ice and Fire: The Faith of the Seven is weaponized by different factions.

- Star Wars: The Jedi Order’s role in the Republic mirrors a theocratic force.

Different faiths can coexist or clash, creating tension and societal divisions.

Myths

Myths are the stories cultures tell about themselves, their gods, and their heroes. They shape identity and ideology.

The Power of Myths

Myths often justify social order, inspire rebellion, or instill cultural pride. The Legend of Zelda presents myths of creation that influence the world’s history. In A Song of Ice and Fire, legends of Azor Ahai influence the expectations of rulers and warriors.

Not All Myths Are Universal

Different cultures have different mythological focuses:

- In Dune, water scarcity makes water a sacred concept, unlike myths in water-abundant settings.

- Avatar: The Last Airbender shows each nation’s spiritual connection to their respective elements.

Theology and History

Religion and myths influence historical narratives:

- Who writes history, and why?

- How do myths change over time to suit those in power?

The Empire in Star Wars rewrites history to justify its rule, erasing the Jedi’s legacy. By weaving together political structures, religious beliefs, and mythology, you create a living, breathing world that feels dynamic and immersive.

Part VI: Practical Worldbuilding – Maps, Names, and Details

And now finally, you can come up with the details of your world. Think back on the key elements of worldbuilding we talked about. This is where geography comes into play.

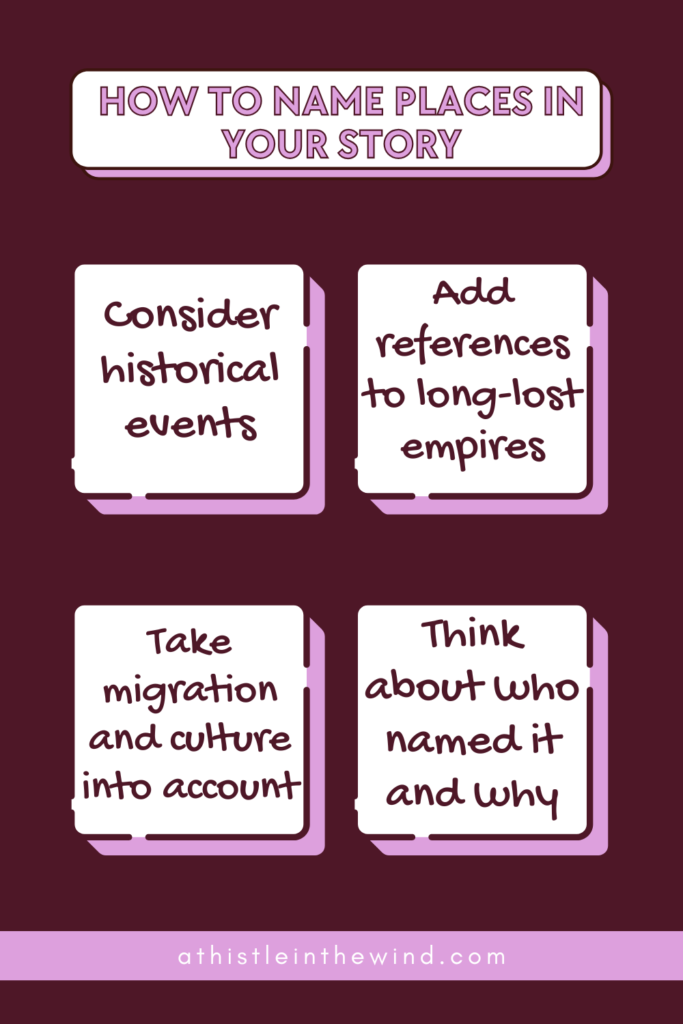

Place Names

Place names are more than just labels on a map; they carry history, culture, and power. The names of cities, regions, and landmarks evolve over time, reflecting conquests, migrations, and societal changes.

A place that once bore the name of a long-forgotten kingdom may now be called something entirely different due to colonization or political shifts. Consider how names change based on language evolution, cultural blending, or deliberate renaming by rulers seeking to erase the past.

For example, in A Song of Ice and Fire, King’s Landing reflects its origins as a conquest site, while Old Valyria’s name evokes a long-lost empire. In The Lord of the Rings, Gondor’s place names, such as Minas Tirith and Osgiliath, carry linguistic consistency, reinforcing the world’s depth.

When coming up with names, consider who named a place and why. Was it named for a ruler, a deity, a geographic feature, or an event? A town built around a sacred river might have a name tied to water deities, while a fortress city might have a title reflecting its military history. Language drift, translation errors, and slang also play a role in name evolution.

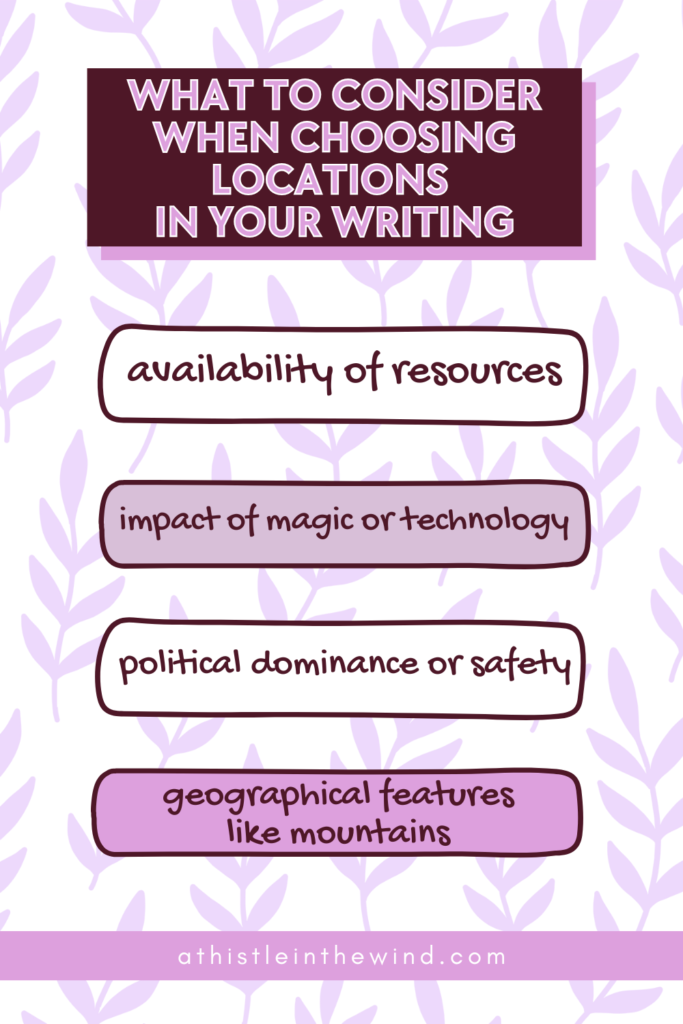

Why Cities Are Where They Are

Cities don’t appear randomly; they emerge where resources, trade, and strategic advantages align. In the ancient world, most cities formed near fresh water sources, fertile land, and natural defenses. River valleys, coastlines, and crossroads became hubs of civilization because they supported agriculture, trade, and travel. In contrast, cities built purely for military or political reasons—like capitals relocated by emperors—often struggled unless they developed strong economic foundations.

Magic and technology also influence city placement in speculative worlds. A city might be built around a leyline of magical energy, or an interstellar hub could exist at the nexus of space travel routes. In Star Wars, Coruscant’s importance stems from its centrality in galactic politics and trade, while in The Hunger Games, the Capitol’s location ensures dominance over outlying districts.

Over time, cities adapt to new technologies and societal changes. The Industrial Revolution brought explosive urban growth, while post-industrial cities had to reinvent themselves. A futuristic city might be structured around artificial ecosystems, orbital space stations, or even floating platforms in a flooded world.

Mountains and Settlements

Mountains serve as both barriers and havens, shaping the cultures that develop within them. Throughout history, mountain ranges have acted as natural borders, limiting invasion and fostering isolationist communities. Settlements in the mountains tend to fall into three main categories: resource towns, trade towns, and religious sanctuaries.

Resource towns emerge where valuable minerals, gemstones, or other resources are found. These settlements might thrive on mining but struggle with transportation and harsh conditions. Trade towns exist in mountain passes, where merchants and travelers must pass through, creating bustling markets. Religious towns, often built on high peaks or secluded valleys, offer isolation for monks, prophets, or mystics seeking spiritual enlightenment.

Mountains also lend themselves to guerrilla warfare, as seen in both historical conflicts and fiction. The rebels in The Hobbit use the Lonely Mountain as a defensive stronghold, much like real-world mountain fighters throughout history. In speculative settings, mountains might house hidden civilizations, underground networks, or even sentient peaks that influence the land around them.

When designing mountain cultures, be wary of environmental determinism—the assumption that geography alone defines a people’s character. While isolation can shape traditions, real-world cultures demonstrate adaptability beyond mere geography. A mountain-dwelling people might be hospitable traders rather than reclusive hermits, or they might have advanced tunnel networks allowing easy access to the lowlands.

Bringing It All Together

Interested in more blogs about writing books? Check out these blogs I’ve written:

- On Writing the First Chapter of a Novel

- On Writing Emotions: A Writer’s Guide to Mastering Feelings in Fiction

- How to Write the Perfect Scene: A Writer’s Guide

This was probably one of the most extensive guides I’ve ever written here. Normally, I go for quality over quantity but it does show how important worldbuilding actually is, and how comprehensive it can be.

Obviously, there are so many more things that I could talk about. But if you’re starting out with worldbuilding for your novel, this is guide includes everything you need to consider. In the future, I’ll be talking about more specific things like revolutions, something which I’m struggling with. But for now, it’s a wrap.

Remember, worldbuilding is about bringing all the key elements I spoke about in the beginning into one cohesive, unified universe that readers can get lost in. Depending on the genre of your book, you’ll find certain parts more relevant than others. So, what do you think? Are there any worldbuilding tips you’d like to share? Let me know!

One Comment

Haillee

Once again, super informative! I will be using this guide for my book 😀