How to Develop a Magic System in Fiction

Let’s be honest: one of the most fun parts of a fantasy book is the introduction of magic. Seriously, if your story’s blurb has an intriguing magic system, I’m reading it. That’s how I wound up picking up Air Awakens at the beginning of the year. Sure, I abandoned the series because of how quickly the world and plot disintegrated, but I stuck around for three books because the magic system was so good.

But that’s the thing about magic systems, isn’t it? It can drive your entire plot if it’s good. Of course, your story shouldn’t solely depend on it but that’s how critical a magic system can be.

So yeah, if you’re going to include magic in your story, it’s super important for you to get it right. How many times have you read a book where you felt like the magic system should’ve been developed a bit more? Or a book where it felt inconsistent?

And trust me, you don’t want your readers to feel the same. So, in this blog, we’re taking a closer look at how to write a magic system in fiction.

What Exactly is a Magic System?

At its core, a magic system is the structured set of rules, principles, and mechanics that govern how magic works in your story. Think of it like the foundational geography or social customs of your world. It establishes the boundaries for how magic can influence your characters and their environment. It provides credibility and coherence to your story, preventing characters from wielding infinite powers and ensuring that magic feels grounded.

Defining the Core Concept

Your story’s magic system sets the boundaries: what it can and cannot do, how it’s accessed, how it’s controlled, and what happens when it’s used. This structure guides the role of magic and establishes expectations for both the characters and the readers, creating opportunities for powerful narratives.

Hard Magic Systems

A hard magic system has clearly defined and strict rules that limit its use, creating structure, strategy, and consequence. The constraints on how magic works must be consistently followed, making the use of magic feel more like technology or science.

The benefit here is that readers can anticipate what characters are capable of. When your characters use magic in your story to resolve conflicts or solve problems, the reader needs to understand how this happened, making things believable and earned. The defined limitations force characters toward creative problem-solving.

We can see excellent examples in several popular fantasies:

- Allomancy in Mistborn: Users ingest and “burn” specific metals to gain powers, but these metals are finite resources, requiring resource management and strategic planning.

- Sympathy in Kingkiller Chronicle: Sympathetic bonds allow control over objects, but the rules dictate that energy can’t come from nowhere.

If magic is going to directly impact your plot, action, or problem-solving, a hard system is likely your best choice. It clearly defines abilities allowed for creative strategy and believable, well-foreshadowed outcomes.

Soft Magic Systems

A soft magic system, in contrast, is more mystical, vague, and undefined in its rules and boundaries. It prioritizes a sense of wonder, mystery, and unbounded possibility over scientific structure. Limitations and costs aren’t clearly defined, and the magic can feel symbolic, spiritual, or ethereal.

Readers cannot easily predict the full extent of the magic or its consequences. Soft magic systems lend themselves well to stories focused on themes of faith, spirituality, cosmic forces, or self-discovery, where the magic is transcendent and subjective.

Prime examples include:

- The Lord of the Rings: The full extent of Gandalf’s abilities aren’t defined, and the magic often appears symbolic, tied to spiritual forces created by the Valar. Magic is used sparingly, evoking mystery.

- The Force in Star Wars: This spiritual energy field guides users, but its full capabilities are never quantified.

If magic serves a symbolic or spiritual significance in your story, a soft system is perfect. To keep a soft system compelling, focus on the experience and emotions magic evokes, revealing specific rules gradually, and leaving room for the unknown.

The Hybrid Approach

Of course, these two categories are ends of a spectrum, not strict boxes. You can absolutely blend a hard and soft system. For example, by having defined rules for some magic users while others tap into more mysterious cosmic forces. Ultimately, determining the role you want magic to play in your story—as a power to strategize with, or a spiritual force to inspire—will shape your choice.

The Essential Ingredients for Setting Up a Magic System

Before you begin building your system, you need to consider the fundamental elements that give magic structure, purpose, and consistency.

- Powers and Abilities: What exactly can magic do? Define the abilities and their effects, considering offensive, defensive, utilitarian, and ritualistic applications.

- Source or Origin: Where does magic come from? Is it a natural force, genetics, deities, external objects, or intensive training?

- Accessibility: Who can use magic? Is it an inborn talent, something learned through study, or limited to certain bloodlines, social classes, or environments?

- Limitations: What are the boundaries, costs, or weaknesses of the magic? Limitations are crucial because they create tension, strategy, and consequences. They prevent magic from being an overpowered, problem-solving device.

- Price and Consequences: What sacrifice or risk is taken to access the power? This can be physical exhaustion, sanity, social standing, or an ethical compromise. In Fullmetal Alchemist, alchemy requires equal exchange—to gain something, something of equal value must be sacrificed.

- Growth and Mastery: Can users improve their abilities with time and practice? The learning curve and progression path can serve as a powerful narrative tool for character development.

- Aesthetic and Components: What visuals, symbols, gestures, words, or physical tools (wands, staffs, artifacts) are needed to perform magic? These elements interact with the physical world and add cultural flavour and visual style. For example, magic in Doctor Strange involves intricate hand gestures and mandalas.

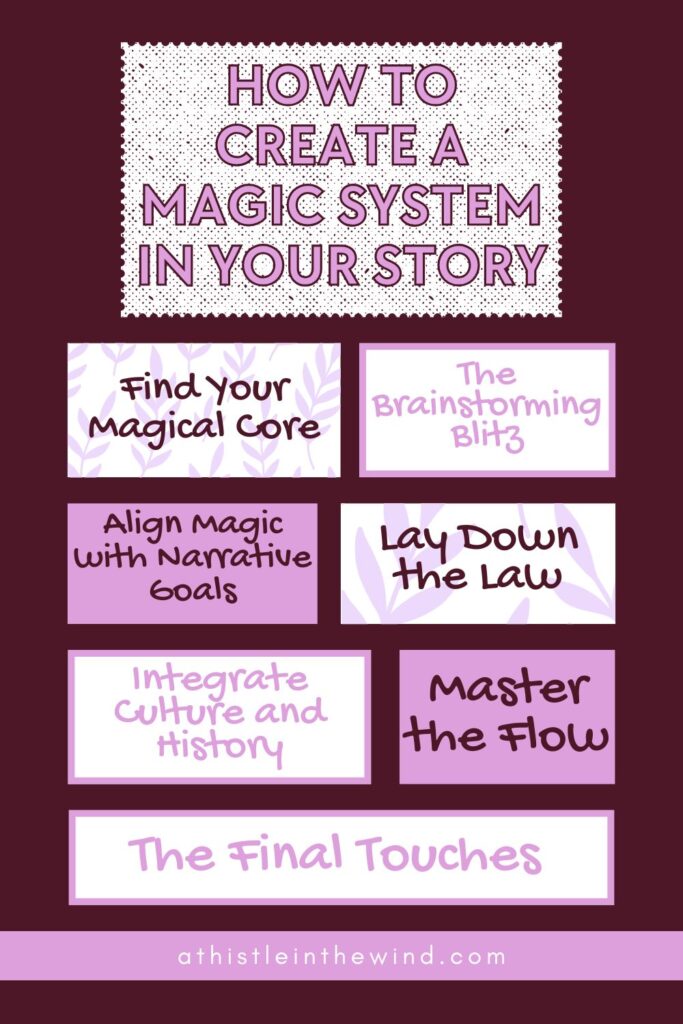

How to Set Up a Magic System: A Step-by-Step Guide

Building a robust magic system follows a coherent process, moving from initial concept to rigorous testing. These stages guide you through developing a unique and functional system.

Step #1: Find Your Magical Core

Every great magic system starts with a central concept that guides its entire development. This inspiration can be a picture, a character concept, a core emotional moment, a high-level plot idea, or even a niche personal interest. Identify the core visual or driving force you want your magic to revolve around. Relating magic to something concrete, like tasting and combining different flavors, can also serve as a novel seed crystal.

Step #2: The Brainstorming Blitz

Once you have your central concept, it’s time to generate a few ideas related to literally anything about your magic. Write down thoughts for effects, limitations, character moments, visuals, themes, and conflicts. The goal is quantity over quality at this stage. You want more ideas than any single story could handle. Tools like mind mapping can be incredibly useful for recording and expanding upon all these potential concepts.

Step #3: Align Magic with Narrative Goals

A magic system should serve your story, not overshadow it. Alignment is about ensuring the magic system connects with and supports your story’s elements.

- Define the Purpose: Determine how magic fits into your world and narrative. Is it common or rare? How does it impact politics and daily life? Keep asking how the magic system improves your story.

- Research Your Genre: Understand your story’s subgenre conventions. The role of magic varies vastly. Compare the ambiguous magic in gothic horror, like Mexican Gothic, to the deeply integrated magic found in low-stakes medieval fantasy. Researching comparable books helps you understand what readers expect and allows you to either play into or subvert common tropes.

- Cultural and Historical Influence: How is magic perceived across different societies? Has it shaped history, rituals, or beliefs? Cultural attitudes toward magic add nuance and realism, such as the fear and persecution of Apostate mages by the Chantry religion in Dragon Age.

Step #4: Lay Down the Law

This is where you dig into what your magic actually is and, crucially, what it is not.

Definition

Map out the specific effects you will use and how the magic connects with the world and characters. Consider the high-level frameworks:

- Law-Governed Systems: Magic follows set, unchanging laws, like the physics of the fantastical.

- Chaos Magic Systems: Unpredictability reigns supreme, with rules acting more like loose guidelines.

- Hierarchical Systems: Power comes in layers; the higher one climbs, the more might they wield.

- Economic Systems: Magic operates like a precious resource that can be traded or hoarded, mirroring social hierarchies.

- Ecological Systems: Magic is a force of nature; its use or misuse impacts the world’s ecology.

Restrictions (Limitations over Powers)

Limitations are often the most interesting part of a magic system. They keep characters vulnerable and prevent the system from spreading in unintended directions.

- Time or Location Restrictions: Magic may only function within a certain location, such as a shallow river that unlocks the ability to see the future when standing in it.

- Resource Dependency: Magic might require a specific resource, like being able to summon water only while bleeding, where the amount of water is proportional to the amount of blood lost.

- Legal Restrictions: Society itself may prohibit certain types of magic, rendering them illegal.

- Personal Sacrifice: Magic may require a personal, moral, or ethical trade-off, such as trading vitality, memory, or degrading your eyesight.

- Finite Use: Every user might have a limited set number of magical actions with no way to renew them. This builds a real sense of consequence and stakes.

Step #5: Integrate Culture and History

You needd to weave magic into very aspect of your world-building.

- Types or Schools of Magic: Create different branches of magic, such as elemental (fire, water), thematic (healing, illusion), or unique concepts. This allows for specialization and diversity among users.

- Aesthetics and Components: Define the visual and sensory details. What does magic look, feel, taste, or sound like? Emphasize descriptive details to make the magic feel real.

- Conflict and Opposition: Create opposition to magic, which drives the plot. This could be anti-magic factions, rival magic users, or competing clans defined by combat abilities. An interesting system creates both great power and great conflict.

- Balance and Harmony: Are there checks and balances to prevent misuse? How does magic affect the natural order? Balance maintains tension and creates ethical dilemmas, such as the Avatar maintaining harmony between the physical and spirit realms.

Step #6: Master the Flow

Magic should integrate with your character development. A character’s growth and struggles in mastering their powers should be central to their emotional journey.

- The Learning Curve: Decide if mastery requires innate talent and years of training in magical schools, providing built-in character progression, as seen in Name of the Wind.

- Symbolism and Themes: Does your magic system represent deeper themes? Use your magic to physically manifest your story’s messages. For example, the four elements in Avatar: The Last Airbender symbolize mankind’s relationship with the natural world.

Step #7: The Final Touches

- Testing and Refinement: Once you have built your system, you must test it. Stress-test your magic to see what breaks, what is theoretically possible that you don’t want to be possible, and what loopholes exist. Watch for anything that would trivialize the plot or let your characters become God-like (omnipotent, omnipresent, or omniscient), as this gets boring quickly. Also, watch for paths to unlimited wealth. Testing helps you find those giant plot holes before your readers do.

- Iteration: Nothing is perfect on the first try. Go back and revisit previous stages—fix inconsistencies, refine definitions, and ensure alignment with your story. External feedback from beta readers is crucial here to gauge clarity, consistency, and appeal.

- Naming Your System: Choose a fitting, memorable name that captures its essence or cultural relevance. “Alchemy” evokes ancient science, while “The Force” suggests an omnipresent energy field.

- Show, Don’t Tell: When explaining your system, avoid dense exposition. Reveal aspects gradually through scenes that demonstrate magic organically. Focus on the character’s sense of wonder and curiosity as they discover the magic, rather than explaining every technical detail upfront.

18 Techniques to Use to Create A Distinct Magic System

Even if you start with a somewhat typical idea, applying constraints and concepts can make your system feel unique. To create a truly distinct magic system, blend familiar elements with creative twists, drawing inspiration from diverse fields like science, culture, and personal interests.

Linking Magic to the World and Society

- Relate Magic to Social Status: Spells and abilities are linked to a character’s standing within society.

- Place-Specific Magic: Magic is only effective within a certain location. For instance, a shallow river might unlock the ability to see the future only while standing in it.

- Group Relying Magic: This magic requires elaborate synchronization among a group to function. A dance-based system, for example, where the power is directly related to how coordinated the dancers are.

- Seasonal Based Magic: Magic is influenced by different seasons or natural cycles. Setting a climactic moment at the worst point in the cycle adds tremendous suspense.

- Link to a Natural Phenomenon: The strength or availability of magic is linked to an uncontrollable natural aspect of the world, such as temperature, ocean tides, rain, or storms.

- Linked to Astronomical Alignments: Magic is tied to the position or movement of celestial bodies, planets, or constellations.

- Ancestral Linked Magic: Magical strength is linked to the respect, worship, and adoration given to one’s ancestors. Praying at a family shrine might increase stored magical powers, which the ancestral spirits can then doll out.

Restrictions and Sacrifices

- Sacrificial Based System: Magic requires a personal, moral, or ethical compromise or sacrifice to function. Using the magic might degrade eyesight, or a user might sell their soul for power, similar to Faustus making a deal with the devil.

- Limited Use Magic: Every user gets a set number of magical actions. Once a character’s out, it’s gone forever. For instance, being born with different tattoos on each fingertip, where activating a tattoo gives a power for a minute, and then the tattoo disappears.

- Build Unique Magic Through Limitations: Take a typical magic concept (like conjuring water) and institute restrictive boundaries around it. As noted above, limiting water summoning to only occurring while bleeding makes the system unique.

- Interpersonal Transfers: Magic is a zero-sum game where people can exchange attributes like Brawn, Grace, Wit, or Beauty from person to person. People who take many transfers become all-powerful.

Novel Sources and Uses

- Taste-Based Magic: This requires tasting and combining different flavors and substances (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, savory), with different combinations producing unique spells. Refining your food palette makes you a stronger magician. Tasting something sweet might allow control over emotions to make others affectionate, while tasting something bitter might grant the ability to detect lies.

- Build Magic Around a Core Emotion: Identify a core emotion: fear, disgust, joy, terror that you want your magic to produce in readers, and work backward to create a magic conducive to that experience. For example, a system where characters must confront their deepest fears to unlock power will produce dread and terror.

- Art Based Magic: Magic’s created by the use of art like painting, sculpture, or performance art, with the quality of the artwork affecting the final result. In one example, stacking rocks in creative patterns summons spirits.

- Memory Manipulation and Trading: Magic is based on altering, exchanging, or transferring memories. This could lead to a black market for illicit memories. Memory collectors could hoard memories from the dawn of time.

- Replace Modern Technology with Magic: Take a function technology provides today and use it as inspiration.

- Work Backwards from the Consequences: Identify a specific narrative aim—say, a sorcerer going crazy from magic overuse—and develop a system where using the powers poisons her sanity. Always ensure the magic system serves the story’s aims.

- Based On a Niche Personal Interest: Use a non-common hobby or personal fascination, such as pottery, as the basis for an interesting magic system.

How to Make Your Magic System More Believable

A great magic system must be believable to keep readers immersed. This relies heavily on consistency, balance, and strategic use.

Consistency: Avoiding the Deus Ex Machina

A massive pitfall for new fantasy writers is inconsistency. If a character needs a specific incantation to cast a spell early on, they should not suddenly cast the same spell later with just a thought, unless there is a clear, explained progression.

Magic should never serve as a convenient deus ex machina plot device that arbitrarily solves story issues. If a previously unmentioned magical artifact appears just in time to solve a crisis without prior foreshadowing, readers will be frustrated. Establish your rules with care, stay organized, and reference your established system often.

Being Wary of Overcomplication

While deep magic systems are appealing, avoid making the system so complicated that it overshadows the plot and character development. If readers are spending too much time trying to understand the mechanics, they aren’t invested in the story.

If your system is overly complex (for instance, a dozen types of magic, each requiring unique ingredients, incantations, and rituals, plus 82 different magical beasts), you need to simplify.

Tried-and-true fixes for overcomplication include:

- Simplify other parts: If you have many abilities, give them all the same harnessing process.

- Simplify the plot: If the magic system is complex, keep the plot simple, and vice versa.

- Conflate elements: If multiple magical creatures or elements serve the * same* plot purpose, condense them. Sixteen different beasts is a lot for readers to track; condense them into four types with a clear hierarchy.

- Dole out the world in waves: Reveal aspects of your magical world slowly, allowing readers to build their understanding gradually, rather than overloading them upfront.

Remember, complex doesn’t mean complicated. A good system is often an expansion of one central idea, made richer when the same principles apply to different characters.

Handling Power Escalation

As your story progresses, your main character’s power will likely grow. Making this escalation believable is key to maintaining tension.

1. Character Arc Alignment

You can integrate the escalation of power with character growth. The ability to master certain powers might require specific moral ideals or character traits. For example, characters gain new abilities only when they accept and live up to certain ideals, such as Kaladin in Stormlight Archives gaining power when he accepts that protecting others includes those he hates. Failure to use powers at crucial moments might be caused by emotional turmoil. For example, in Avatar: The Last Airbender, Zuko struggles to generate lightning until he resolves his internal conflict. This technique is generally more useful for soft magic systems, as emotions aren’t easily quantifiable in strict hard systems.

2. Escalation and Tension

It is almost universally true that the magic system escalates as the tension escalates, allowing the wizard to face grander things and defeat more dangerous threats. However, scaling up the stakes continually can lead to power creep.

3. Avoiding Power Creep

Power creep occurs when power escalation eclipses the story and undermines narrative tension.

- Stakes: Power creep often manifests as exponentially growing stakes (saving a family, then a city, then a planet), at which point readers stop caring because the scale is too great to grasp. Emotional weight often matters more than scale.

- Immersion: Power escalation risks losing immersion if the foundational rules that made the system unique are lost for the sake of grander abilities.

4. The Power Ceiling

Establishing the magnitude of your power system early on is crucial. This power ceiling helps maintain immersion because the escalation, when it occurs, doesn’t undermine the established rules.

Once the ceiling’s established, the story needs to stick to it. Breaking it (as seen in later seasons of Legend of Korra where Korra fights the embodiment of chaos with laser beams after mastering the elements in season one) risks losing what made the original story special.

5. Maintaining Tension Without Escalation

If a character reaches their peak halfway into the story, you can still build through two primary techniques:

- Incomparable Abilities: Introduce antagonists whose abilities do not operate on the same scale as the protagonist’s. For example, a hero with super strength might face a foe who uses mind control in one arc, and then in the next, faces an extraordinarily cunning serial killer who uses the law against them. The tension remains because the obstacles are incomparable, and being powerful does not guarantee victory against a vastly different challenge. The protagonist must rely on cleverness rather than raw application of power.

- Character Challenges: Create antagonists who challenge the protagonist on a deeply personal or moral level. You can build tension here from the difficult moral choices characters are repeatedly forced to make, regardless of how powerful they become. This works well for characters who are already overpowered. Think Captain Marvel in Avengers: Endgame; Carol kills Thanos in the beginning of the movie, but it’s pointless because the Avengers still can’t bring everyone back.

These strategies are most effective when used together: an antagonist whose abilities require cleverness and who challenges the protagonist in a personal way.